The Beckham Effect

Winner Takes It All: When ‘Tough Love’ Becomes Just… Tough. Youth Sports in Denmark vs UK and USA

Picture the scene: it’s a drizzly Saturday somewhere in the UK or the US. A group of eight-year-olds fumble their way through a football match, some chasing a ball, others staring at clouds, and one – inevitably- picking their nose. But on the sidelines? It’s carnage. The referee’s getting heckled, parents are yelling and at least four people are performing wild gesticulations as though staging an impromptu new mime show called: Win At All Costs. This was the feel of the football match of a friend’s eldest at the weekend.

Now, hop on a metaphorical flight to Denmark. Here, a similar football match might be taking place, most weekends. But the scene is likely to be…different. At least, it was in my experience of youth-sports in the Jutland countryside. There, parents would sip coffee, chatting amicably. There might be polite clapping and occasional cheering - but it was supportive and addressed to the team, rather than hectoring or heralding individual players. No one was threatening to ‘have a word’ with the ref after the match. The focus wasn’t on turning their child into the next Lionel Messi, but on making sure everyone— even the kid picking their nose—had a good time.

The contrast between the Anglo-American and Nordic approaches to youth sports reflects deeper cultural differences in parenting. In the UK and US, childhood has become a competition. From violin lessons at age three to tutoring at eight, there is a pressure to excel. One Danish parent whom I interviewed for How to Raise a Viking (out in paperback now) had raised her children in Silicon Valley for many years. She spoke in horror of nurseries she encountered that were promising to ‘get kids on track for Stanford’ - aged two. From then on? It was winner-takes-it-all-the-way.

The pressure to specialise young, win at all costs, and prove oneself as a future prodigy is immense. But does this actually help? Or are we raising a generation of burned-out, stress-riddled future humans who’ll flinch at the sight of a football?

The David Beckham Effect: When ‘Tough Love’ Becomes Just… Tough

If you’ve watched the Netflix Beckham documentary, you’ll know that a) David Beckham has a fine line in shackets and mandigans, b) Victoria keeps a lovely house and c) David’s dad, Ted, was intense.

Little David spent his childhood practicing football under his father’s unwavering gaze, repeating drills over and over while Ted withheld praise. If David scored a goal, the response wasn’t “Well done!” but: “You should have scored three.”

It’s the kind of parenting that many in the UK and US admire. “See?” they say: “That’s how you create greatness! Hard work! No excuses!” But here’s the thing - while Beckham did become one of the greatest footballers of all time, he also admits that his father’s relentless pressure was brutal. For every Beckham, there are thousands of kids who get pushed too hard and end up quitting sports entirely.

How Danes Do It

In Denmark, this philosophy doesn’t exist in quite the same way. Youth sports (especially for the very young) are about inclusion, teamwork, and - brace yourself - fun. The idea is that if children enjoy the game, they’ll stick with it, get better naturally, and develop essential life skills along the way.

Which all sounds very sensible. Except for when it doesn’t. In 2023, The Danish Sports Confederation announced that it wanted to do away with competition for under 13s altogether to reduce pressure on children and encourage more into sports.

READ: Sport ‘for fun’, sauna culture, plus we need to talk about Ozempic...

This felt excessive, especially considering that there was already no such thing as ‘sports day’ at schools in Denmark. Instead there was ‘motion day’ every year - where everyone ran about a bit. At my children’s last ‘motion day’, everyone was given a bucket hat and a pair of sweat bands sponsored by Danish Crown – famed purveyors of Danish bacon (‘bacon’ and ‘PE’ - together at last) as a ‘thanks for participating!’

Why I’m conflicted (or am I?!)

But, bucket hats aside, don’t we all need a little incentive? How do children' learn to be ‘sporting’ without any competition before the age of 13? And how to parents learn how to handle themselves on the sideline? Because *whispers it* I’m not immune to ‘overexcited parent’ mode, in spite of 12 years of living Danishly.

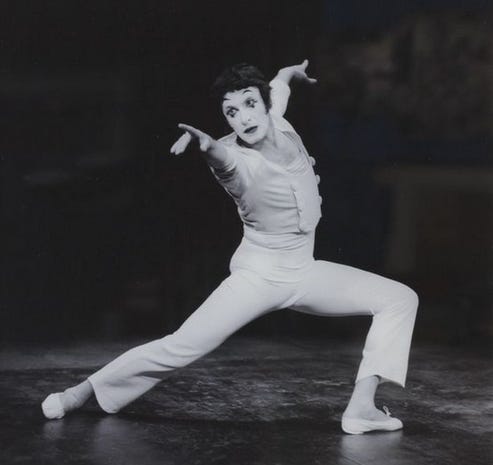

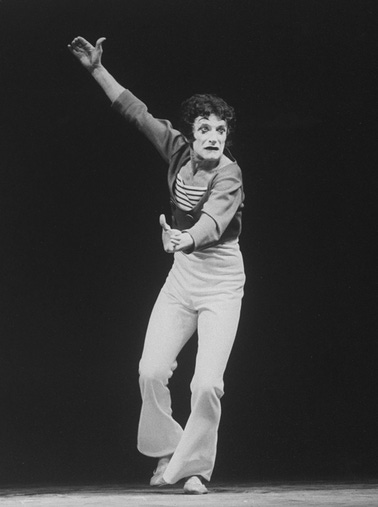

I know very little about sport (this Guardian piece was a blip). Yet I still feel the urge to join in/yell/stage a one-woman Marcel Marceau theatrical happening on the sidelines of any sporting endeavour. A lot like this:

We are all just products of our upbringing. And perhaps my family just carry the ‘taking Monopoly too seriously’ competitive gene. I recently learned of the existence of a primary school pub quiz and was far keener to join than I care to reflect on. I would dearly love to drift through life, a hybrid of Henry Winkler’s The Fonz and Mads Mikkelsen’s icy Nordic cool. Alas, it isn’t to be.

So what’s the balance? I’m still trying to work it out. But the answer can’t possibly be to put off great swathes of the next generation from using their bodies or enjoying sport.

As someone who did not excel at physical education or team games at school, I was discouraged from even trying. Which meant that I only discovered this brave new world of ‘being active for fun’ in my 30s. I had ALL the crazy ideas about bodies before then (Oh hi Gen X/Elder Millennials! I see you *waves*). That way, madness lies. So it’s definitely not that.

READ: Crisps, culture and the great divide: a tale of snack habits

For sportier friends who ‘nearly made it’, there was often a sense that they were written off, as failures, having to ‘retire’ from their chosen sport in adolescence. Which, I don’t know about you, but seems to me a pretty rough time to be written off. I’m all for trying and failing (repeatedly - this is how we grow). But being labelled ‘a failure’ is something entirely different.

The Downsides of Hyper-Competitive Parenting

The problem with the Anglo-American approach to sport isn’t just that it makes sideline parents act like lunatics (hi!) but that it has a negative impact on children. Research now shows that excessive parental pressure in sports leads to anxiety, low self-esteem, and, ironically, worse performance.

A study published in the Journal of Sports Sciences found that kids who felt their parents were overly critical about sports developed higher stress levels and were more likely to drop out entirely. Another study in Psychology of Sport and Exercise found that children who experienced ‘controlling’ parental behaviours (e.g. constant criticism, unrealistic expectations) were more likely to suffer from burnout and lower self-worth.

Meanwhile, Danish researchers found that kids who played sports in a more relaxed, socially supportive environment were more likely to continue participating into adulthood. The emphasis on teamwork and personal enjoyment led to higher levels of confidence and long-term well-being. Parents in Denmark aren’t yelling at their kids to “man up” or “try harder”—they’re just happy their child is moving their body, making friends, and (hopefully) learning the value of teamwork.

The Money Problem: Sport as an Investment Strategy

Another alarming phenomenon is the transformation of children into financial investments.

Friends in the US share how youth sports there are a billion-dollar industry, with parents forking out thousands on elite coaching, travel teams, and specialised training camps. Why? Because of the deeply ingrained belief that if a child doesn’t commit to a sport early (and entirely), they’ll fall behind. For many families, the Holy Grail is the coveted college scholarship (because otherwise the costs are so prohibitive).

Studies show that many parents rationalise their spending on youth sports with a: ‘Sure, we’re spending $20,000 a year on soccer, but we could get a scholarship to Stanford!’ (in fact, less than 2% of high school athletes actually get athletic scholarships, according to the National Collegiate Athletic Association).

Denmark, on the other hand, operates on an egalitarian model where sports clubs are affordable, inclusive, and primarily community-driven. The idea of spending thousands on elite coaching for an eight-year-old would be considered absurd. Instead, Danish kids are encouraged to play multiple sports, develop different skills, and - most importantly - decide for themselves if they actually like the sport before committing to it.

Who Moved My Goalposts?

The fundamental question we need to ask is: what do we actually want for kids?

If the goal is to create world-class athletes, then sure - push them hard, demand perfection, and treat every under-10s football match like the World Cup. But if the goal is to raise happy, confident, resilient kids who enjoy staying active for life? Then maybe - just maybe - Denmark is onto something.

Because here’s the thing: the vast majority of children playing sports today will not become professional athletes (sorry). And that’s okay: there’s a whole world out there. What’s not okay is the staggering number of kids who quit sports entirely because pressure sucks all the joy out of it. Research shows that 70% of kids in the US drop out of organised sports by age 13, with the primary reason being that it’s simply “not fun anymore” (according to a poll conducted by the National Alliance for Youth Sports). In the UK, the stats are similar .

Sports England found that children aged 13-16 the least likely to be active – just when their teenage minds and bodies might benefit most.

So perhaps we should all take a breath. Step back. Because if we treat children’s sports like a high-stakes competition, we risk losing the thing that actually matters: kids who want to play.

And who knows - if we let them enjoy the game on their own terms, we might just end up with happier, healthier and more well-rounded humans. The ultimate win.

Until next week, vi ses,

Helen

READ: How NOT to Boost Productivity: A Handy Guide for Employers

I remember a couple of years ago while still in the UK (now Aarhus) my son’s football team had a “silent support” week (once a season throughout the FA grassroots programmes). You could politely clap but nothing else during the match, and without exception all the kids said they preferred playing that way!

I’m not a parent and I’ve observed coworkers, friends, and family put their kids in every sport imaginable as early as possible. These kids (and their parents) seem to have zero unscheduled time which to me seems to be deleterious. When does the kid just play? Or read for the joy of it? Or just daydream? When do the parents get downtime from all of the travel leagues?

I’m in the U.S. and now more than ever I feel like I don’t belong because of the hyper-competitiveness (amongst other things). I think the Nordic countries might suit me better.