'Are you happy?' Depends where you live

Why WHERE we are has as much of an impact on happiness as HOW we are.

Following on from last week’s World Happiness Report, this is the first of my scheduled posts while I’m off wrangling 90,000 of a final draft of a novel along with insomnia and three children so I wanted to share this piece - one of the most popular from my archives.

It’s a huge privilege to get to travel a lot for work and give talks all over (Copenhagen, see you again soon!) and I’ve been struck by some of the questions that have been raised and the discussions I’ve been having at various events.

A very smart (in all senses of the word) woman asked a very thoughtful question about happiness and How to Raise a Viking recently, then shared a little about a tough time she’s currently having. She asked: ‘how, at a time like this, can I be happy?’

I wanted to hug her first of all. And then I wanted to assure her that even ‘happy Danes’ would struggle under the circumstances she was describing.

READ: The Danish happiness paradox

Even in the Nordic countries - the happiest countries in the world - bad things still happen. And we all experience loss and disappointment at times.

But the more I learn and the more I travel, the more I am struck by how many of can find this a challenge.

The countries that top the happiness rankings often tend to remove many of the reasons for unhapiness. But how we feel is down to more than just happiness rankings. It’s also about the cultural approaches to happiness that we’re raised with.

Take the US…

Current administration aside, the US relationship with ‘happiness’ is very different to elsewhere.

Psychologist Jeanne Tsai from Stanford University’s Culture and Emotion Laboratory has found that an obsession with the pursuit of happiness has led many Americans to view sadness as a ‘failure’ and something that is the individual’s responsibility. As the daughter of Taiwanese immigrants raised in the US, Tsai became interested in how American attitudes differed from those typically found in East Asian cultures.

‘In the US I observed a real emphasis on wanting to feel happiness and avoid sadness, at all costs - far more so than in other cultures,’ she tells me when I get in touch. In East Asia, by contrast, the concept of negative feelings is rooted in Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian traditions and viewed as ‘situationally-based’ or circumstantial.

This means that individuals don’t bear the weight of their negative experiences alone.

‘And negative feelings or experiences can even foster social ties in East Asian culture,’ says Tsai. In East Asia, negative emotions are seen as ‘inevitable and transient elements of a natural cycle’ – or part of life rather than something to be feared as a risk to our mental or even physical health.

We’ve all seen studies saying ‘happy’ people are healthier – and we certainly spend enough time and money trying to be happy in the west. I used to believe this myself. I spent years devouring and dutifully repeating research that ‘proved’ happier people were healthier, ergo we should strive for happiness at all costs. But this isn’t the whole story. Because in cultures where being sad is seen as ‘okay’, sadness has been shown to have far less of a negative impact on health. ‘Researchers have analysed the differences in approach to negative feelings and health in Japan and the US – a good comparison because both are modernised, democratised, industrialised societies with well-developed systems of health care,’ says Tsai. But these societies have very different ideas about negative emotions. As one Japanese psychiatrist told the Association for Psychological Science: ‘Melancholia, sensitivity, fragility – these are not negative things in a Japanese context. It never occurred to us that we should try to remove them, because it never occurred to us that they were bad.’

Unlike in the US, where ‘sad’ is empirically viewed as ‘bad’. And it’s this perception of sadness that can make us sick.

In the US, lower positive emotions are linked with higher BMI and less healthy blood lipid profiles (important indicators of health). But in Japan, studies show that people with lower positive emotions are pretty much . . . fine. So emotions have a different impact on our health depending on our culture; and being sad only makes us sick if we’re terrified of being sad.

Another study from the University of California, Berkeley, found that people who accept rather than judge their mental experiences have better health outcomes. Those who avoided their negative feelings or judged themselves harshly for feeling bad were more likely to report mood disorders and distress. Because if we view ‘sadness’ as something ‘wrong’ or even ‘abnormal’, we’re more prone to pathologise it.

In The Loss of Sadness: How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow into Depressive Disorder (the title says it all), sociology professors Allan V. Horwitz and Jerome C. Wakefield argue that the massive rise in depression in recent years has less to do with the pressures of modern life, and more to do with over-diagnosis. The medical historian Edward Shorter argues that psychiatry’s ‘love affair’ with the diagnosis of depression has become a death grip, asserting that most patients who get the diagnosis of depression are also anxious, fatigued, unable to sleep and have all kinds of physical symptoms. They suspect that many of us are being diagnosed as depressed when we are, in fact, ‘sad’ – a direct result of a dodgy definition in a single, albeit significant, book.

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (the DSM) is a weighty tome used to diagnose all things mind-related in the US. The first edition was published in 1952 in an attempt to unify mental health approaches in the US, but when it came to ‘major depressive disorders’ the DSM focused on symptoms rather than context.

READ: On overwhelm, kiss & fly plus hedgehog houses

This meant that the distinction between ‘actual medical issue’ and ‘ordinary sorrow’ was done away with.

I’ve mentioned this before but for any new readers: here’s why the DSM matters:

Anyone exhibiting five or more ‘symptoms’ for two weeks could be diagnosed with clinical depression – even if their low mood, decreased appetite or poor sleep etc. had a thoroughly understandable explanation, such as heartbreak or financial worries. Earlier editions of the DSM included a ‘grief clause’, stating that people couldn’t be diagnosed with depression within two months of bereavement. But the latest version published in 2013 (DSM-5) scrapped this, doing away with the distinction between understandable sadness and medical condition. Supporters of the DSM-5’s decision argue that grief is a common precursor of depression and given the serious risks of unrecognised major depression, removing the bereavement exclusion was a reasonable decision. But it also means that responses to grief now can be labelled as pathological disorders, rather than being recognised as normal human experiences.

Psychologists in the UK and Europe are supposed to use the World Health Organisation’s International Classification of Diseases (the ICD). But the DSM remains enormously influential and many European practitioners turn to it for diagnosis. So now we’re all taking a leaf out of the American mental health playbook. A problem, since ‘Americans really don’t like to be “sad”,’ as Tsai puts it – a proclivity she puts down to ‘frontier values’.

‘The first settlers from Europe were a self-selecting, intrepid group,’ says Tsai. ‘people who anticipated positive outcomes; were willing to take risks and who handled negative feelings or situations by leaving them in the hope of something better.’ For early pioneers, overcoming hardship was seen as a virtue, whereas wallowing in adverse circumstances was not.

Consequently, the American approach to mental health today tends to be fervently forward-facing. One of the most popular modes of treatment is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), a forward-facing ‘back on your feet’ intervention that seeks to change negative patterns of thinking. Many of CBT’s pioneers came from the US and whereas European psychologists are frequently influenced by Freud’s ‘blame your father’ backward-facing stance, America tends to prefer the promise of a sorrow-free tomorrow. While Nordics, I would argue, are better at being in the moment - Adler style.

READ: The Austrian psychologist Alfred Adler - happiness and Jante’s Law

Because seeing sadness as transgressive – a ‘problem’ to be medicated away – leaves us poorly equipped to manage the next time it comes calling. Pathologising sadness sends a message that ‘discomfort’ cannot – and should not – be tolerated.

But sometimes bad things happen. It’s not that we’re broken: it’s that sadness is a normal response when we experience loss or disappointment. And many of us are living in systems that were not set up for us (more of this in How to Be Sad).

So I’m looking forward to more fascinating discussions on the nature (and nurturing) of happiness. Let me know your thoughts!

Until next time, vi ses,

Helen x

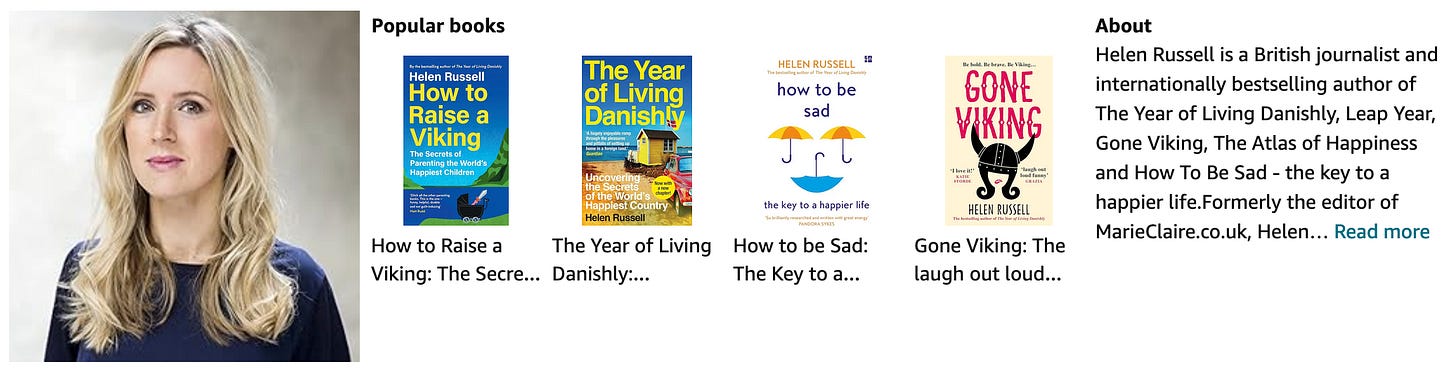

PS: hitting the heart icon can help recommend this Substack to more readers. To read more of my work or if you fancy a new read/audiobook, my back catalogue is here.

Very thoughtful piece and "right on" I'd say. That is why so many young people struggle with their "mental health". They do not have the life experience to know that "this too shall pass". To be upset about anything (anything at all) is seen as something to be medicated, or changed, or "fixed" in some unhealthy way. Think drugs, alcohol, gambling, et al. Life is a complicated journey and always has been.

Happiness is an inside job but a good environment around us does help. Thoughtful piece.