The Culture Cure: Fields of Gold & Florence Syndrome

Taking your culture vitamins, Mozart in a maze and why banana pancakes aren't just banana pancakes (they're medicine)

It’s the Easter holidays and by the time you read this, I will be ferociously scribbling to meet my new book deadline while fielding requests to adjudicate sibling rows/draw a unicorn/play football/bake a cake (‘It’s 7.30am?!’ ‘So?!’). So I’m writing this in advance and going on an imaginative escape to a place where the fields are gold - taking off the paywall temporarily to share one of my favourite Substack classic posts.

All about beauty. Remember beauty? Not Instagram-filtered beauty or tweaked, tuned aesthetic #goals - but real, messy, accidental beauty. The kind that nature occassionally chucks at us that can knock us sideways.

Next month, in Denmark, the oil seed rape flower begins to bloom and rural Jutland is carpeted in yellow. This has always one of my favourite times of year.

After a brutal winter (this can last until April) I would often forget that it could be otherwise. Never-ending winter would start to feel normal, in Denmark. Like Narnia, albeit with a massive Christmassy blowout (see: Christmas in Denmark). I would often put on vests and boots and down jackets on autopilot, even once the thermostat was nudging the teens.

But when blossom fills the trees and the countryside turns a vivid yellow, I’d often be overwhelmed by the sheer beauty of everything.

And this, it turns out, is ‘a thing’…

Stendhal or ‘Florence’ syndrome is a condition whereby we become dizzy, faint and overcome in the presence of beauty or impressive art. The syndrome is named after the nineteenth-century French author Stendhal, who, on visiting Florence, was so awed by the beauty and art all around him that he ‘walked with the fear of falling’. Sometimes the only response to any kind of overwhelming emotion is to fall down and stay there.

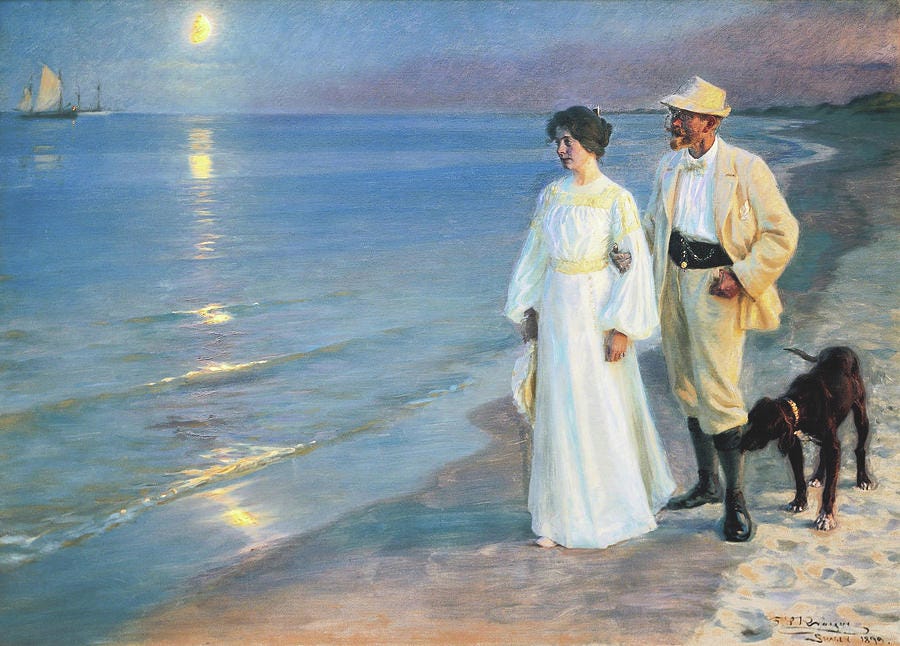

Most of us will remember looking at a piece of art that moved us. Lego Man still remembers the time he had to remind me to ‘breathe’ while looking at the extraordinary light captured in the Skagen Paintings – by a group of Scandinavian artists who gathered in the village of Skagen, the northernmost part of Denmark, from the late 1870s. Mid gallery visit, I came over all peculiar and had to have a sit down.

Culture as ‘cure’ isn’t a new idea. In 2008 the UK’s then health secretary Alan Johnson called for arts to be part of the mainstream in healthcare and in 2009 the Royal College of Psychiatrists recommended ‘participation in arts’ and ‘developing creativity’ for public mental health. More than a decade on, evidence for the impact of arts on well-being is growing. Research shows that ‘art on prescription’ is valued by referrers and participants alike and is remarkably cost-effective with a reduction of visits to the doctor and participants gaining transferrable skills that can help with staying healthy and in work.

Sweden leads the field in terms of arts on prescription in Scandinavia. And there’s now a substantial body of evidence showing how the arts can mitigate some of the negative effects of social disadvantage. A 2015 review found that the community cultural referral schemes led to increases in self-esteem; a greater sense of empowerment; and reductions in anxiety and depression.

‘We can see that it works for many people,’ Anita Jensen, post-doc researcher from the Department of Communication and Psychology at Aalborg University told me. ‘It’s relatively inexpensive – with no known negative side effects’ (other than the whole ‘falling down’ Florence syndrome, presumably).

It’s Not Just Visual Art

Classical music has long been proven to have psychological benefits and the ‘Mozart Effect’ was established in the early 1990s. This is the idea that listening to Mozart significantly increases our spatial reasoning skills. What’s less widely reported is the fact that this effect only lasts for ten to fifteen minutes. But think of what you could achieve in that time? Should you ever find yourself stuck in a maze, for instance, a quick download of Don Giovanni could just save your life (you’re welcome).

Music therapy has been shown to reduce psychological stress, depression and anxiety among pregnant women, according to a study from the Kaohsiung Medical University in Taiwan. Another study, from Juntendo University Hospital in Tokyo, Japan, played mice recovering from a heart transplant either Verdi’s La Traviata, Mozart, or Enya.

They found that mice who were played classical music during recovery from a heart transplant lived almost four times longer. And no, I am not making this up.

Playing sad music when we’re feeling low produces a heightened emotional effect that can foster a sense of belonging, give us identity and even help us heal, according to science. Studies show that when we’re depressed, we’re more inclined to seek out sad music. Researchers from the University of South Florida played both depressed and non-depressed people excerpts of ‘sad’ music (‘Adagio for Strings’ by Samuel Barber and ‘Rakavot’ by Avi Balili), as well as happy and neutral music. Researchers found that depressed participants were more likely to choose the sad music, because it was relaxing, calming or soothing. Another study from the University of Limerick showed that non-depressed people also prefer sad music when blue, because sad music can ‘act like a supportive friend’ and trigger bittersweet memories (like saudade).

READ all about it: Saudade or ‘melancholy for a happiness that once was’ here (and listen to my BBC World Service documentary, here).

Crucially, sad music also functions as an ‘acceptable’ distraction, allowing us to escape the silence and feels somehow more appropriate when we’re down. As much as I love Whitesnake and Van Halen (a lot, thanks for asking. RIP Eddie), upbeat music can feel unthinkable during times of sadness.

Many of us come to rely on this and those who listen to music for three or more hours a day claim it is more essential to them than coffee, sex or TV. Thirty-eight per cent of people reported feeling stress-free while listening to music, despite only 5 per cent of people saying they have a ‘stress-free’ life, according to one Sonos study.

Music can hit us in the solar plexus. It can make our knees buckle, taking us back in time to remember and process emotions that still haunt us. Certain songs reliably make me stop in my tracks. ‘Save Tonight’ by Eagle Eye Cherry catches my breath, every time (unsuitable boyfriend + first love = a collision that knocked me for six). ‘Love Me Or Leave Me’ by Nina Simone, ditto (another unsuitable boyfriend who took the lyrics literally).

Even more low-key music can help when we’re struggling, according to Mikael Odder Nielsen, manager of the kulturvitaminer, or ‘culture vitamin’ programme near where I live in Jutland, Denmark. Nielsen offers people suffering from stress, anxiety or depression the opportunity to go on a culture crash course. ‘We use playlists developed by music therapists to give your brain a break, which in turn allows your body to take a break,’ says Nielsen, explaining that it’s music to ‘reduce arousal’: ‘music that’s predictable, a bit boring even’.

Such as? He thinks about this before responding.

‘Jack Johnson.’

Huh . . . Popping on ‘Banana Pancakes’ isn’t something I’d naturally have gravitated towards when feeling blue, but I try it later and strangely it works (ish). I now think of JJ as the audio equivalent of a mindfulness colouring book. I tell Nielsen I may be a convert and he tells me about some other strands of the kulturvitaminer programme. Partly funded by the Danish Health Authority, municipalities set up programmes encouraging cultural participation for the unemployed or those on long-term sick leave.

‘We wanted to see if we could improve people’s mental health, reduce social isolation and help them get back into the labour market via culture,’ explains Nielsen. Qualifying residents were invited on two to three cultural excursions a week, for ten weeks to see if it made them feel better. And it did. I speak to a man on the programme who suffers from anxiety and was fearful of social interactions prior to starting the course. But culture vitamins, he tells me, changed his life.

‘It was an activity that would get me out of the house, where I was treated as “normal”. And I am not my anxiety: I’m me. So the course helped me feel like “me” again.’

One woman from the programme told me how she suffered from stress and chronic insomnia for six years. ‘Before I went down with stress, I would often go to concerts and museums,’ she says, ‘but then I stopped. Nothing made me happy or even made sense any more.’ This strikes a chord.

‘If you’re depressed, culture is often the first thing you don’t bother with,’ Nielsen explains, ‘you’re too preoccupied with getting through the day. My role is to get them used to this world again – or even introduce it for the first time.’

Structured, ritualised meet-ups and diarised outings also get people back into culture and its benefits by stealth: we may not feel like going out and socialising and engaging with live art when it’s raining and we’ve got Netflix at home. But if it’s part of a course or we’re somehow ‘committed’ – either financially or socially, by promising we’ll meet someone there, we’re more likely to show up. And the ‘stealth’ element means that Nielsen has found the course especially beneficial for men who may be more reluctant to express their negative emotions and vulnerabilities otherwise (thanks, social conditioning).

There are eight strands to the Aalborg culture programme, starting with group singing, proven to help forge social connections and bond large groups. The course includes trips to the city archive to learn about local history and ‘foster a sense of belonging and local pride’, says Nielsen. Participants also go on theatre excursions, visit art galleries and take part in creative workshops, proven to help develop resilience. They even take in performances by Aalborg Symphony Orchestra (‘Very moving,’ says Nielsen, ‘there are often tears’). This is smart, since researchers from the Royal College of Music have found that hearing live music reduces stress.

Another popular strand of the culture vitamin course is ‘shared reading’, where adults are encouraged to snuggle up under blankets in a dimly lit break-out room in the library while a librarian reads aloud to them for two hours at a time. Which sounds a lot like heaven and is very much what I’d like for every birthday and Christmas from now on. Most of us haven’t had books read to us since childhood – audiobooks aside. I say ‘most’ since apparently some people end up with life partners so adoringly romantic that they insist on reading to their beloved – poetry, philosophy, great works of literature, Mills and Boon, you name it. To these folk, I extend felicitations. To the rest of us, I say: ‘Nope, me neither.’

I imagine that being read to is an intimate, nurturing experience that can be pretty emotional, too. As one culture vitamin devotee tells me: ‘I spent so much of my life reading to others in my job as a teacher, but this time I needed help – and I felt . . . taken care of. It was very powerful.’

When we’re depressed or suffering from anxiety, many of us find reading difficult. I can’t concentrate or make any sense of the words on a page when I’m depressed. The silence necessary for reading also feels intolerable. But being read to – via audiobooks in my case – is something different. It’s like being taken gently by the hand and on an adventure. I listen walking home from dropping the kids off. I listen in the car. Or doing the supermarket shop. Or cooking. I’ll listen at night, too, if I can’t sleep. With an audiobook, nothing is expected of us other than to listen. It is, unfailingly, enriching.

Now in Denmark, Aalborg council has chosen to prioritise cultural vitamins and run the programme on an ongoing basis. Another Aalborg local is campaigning for culture as cure throughout Denmark and much of Europe. And I’m with them. Are you? The culture cure is real. So what should we all read next? Answers below.

And Now, Books Are Calling Me…

Later this week, I’ll be on my way to read aloud to some people I haven’t met yet for an author Q&A. And I can’t wait. There’s an alchemy that happens when you share a space and ideas and strangers start to feel like friends. So I’m looking forward to meeting fellow book lovers.

And if you can’t make it to a shared space to experience your culture vitamins this week, let me read to you - The Atlas of Happiness and How to Be Sad, narrated by me, are all available as audiobooks now. How to Raise a Viking is on audible in the UK (and in the US and Canada, under the title The Danish Secret to Happy Kids).

Until next week, vi ses!

Helen

The Reader runs reading sessions most days of the week. There's lots online and also some in person groups. It's all free. I go to one at my local library each week. We read a poem together and then a short story and we take it in turns to read aloud (although there is no pressure to read). I also go to some groups online. It's lovely to be read to and to read to others. I also sometimes then read the poem or short story to my partner. This is The Reader: https://www.thereader.org.uk/

Enjoyed your foredrag today in Helsingør! Thank you!